Notes on the revival of the Auricular style for picture frames

by The Frame Blog

Christopher Rowell discusses the evidence in National Trust collections for the revival of the Auricular style, in particular during the 19th century.

Sir Peter Lely (1618-80), The penitent Magdalen, c.1650-55, o/c, 64¼ x 55⅝ in (163.2 x 141.3 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, partly c.1760?, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT1257099

What is the evidence for a British resurgence of the Auricular style for picture frames? This account concentrates upon Kingston Lacy, Dorset (NT) and begins with a brief description of Ham House, Richmond (NT), where at least one later addition to the collection of 17th century Auricular-framed portraits seems to have been provided with a complementary revivalist frame.

Fig. 1 Edward Cornelius Farrell (c.1775-1854), One of a pair of silver-gilt dishes engraved with the arms of Fetherstonhaugh within an elaborate cartouche after Stefano della Bella, London hallmark & maker’s mark ‘E.F.’, date mark for1824, diam. 15 in (38 cm), Uppark, West Sussex, NT 138009

Auricular revivalism was apparently rather episodic, not only in relation to picture frames. A pair of silver-gilt dishes at Uppark, West Sussex (NT 138009; fig. 1), was acquired or commissioned in1824 from Edward Cornelius Farrell by Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh, 2nd Bt., friend and art adviser of the future George IV [1]. Although the borders of the dishes exhibit Auricular ornament in the 17th century manner, this was not a style for which one can claim a conspicuous ‘revival’.

Ham House

Fig. 2 The Long Gallery looking North, Ham House, Richmond (NT)

The ensemble at Ham (fig. 2) has been described by Jacob Simon as:

‘…a showcase for carved-and-gilt Auricular frames. The various types coexist happily and create a remarkable spectacle, their intricate forms catching the available light…These patterns could be scaled up or down according to the size of the picture. They are mostly of oak with pine back frames, some with their original pegged mortise-and-tenon joints intact, but further research is needed to be confident about materials and also about the precise status of each frame. Researchers have suggested that various of the Sunderland frames may be later in date.’ [2]

In 1994, Alastair Laing and Nino Strachey first realised that although the number of pictures in the Ham Long Gallery in 1844 was identical to the number in 1683, some had flown the coop and others were replacements, suggesting that the frames are not all coeval [3].

Fig. 3 Sir Peter Lely (1618-80) , Sir William Compton, 1650s, o/c, 48½ x 39 in (123.2 x 99.1 cm), in a later (18th century?) carved & gilded Auricular frame, Ham House, Richmond, NT 1139946

Jacob Simon deduced that the Auricular frame of the 1650s portrait of Sir William Compton (NT 1139946) was made to match ‘probably in the 18th century’ (fig. 3). He described the portrait as being ‘housed in an 18th century variation on a Sunderland frame, with rosettes at the top corners’, noting of the Ham Gallery that ‘several of the Sunderland frames are likely to be later copies’ [4]. The history of these additions has not yet been fully clarified, but Laing and Strachey suggest that they may well have continued into the 19th century, which – given the long tradition of antiquarianism at Ham – is very likely. Indeed, there is more evidence at Ham for 19th century revivalism [5].

The National Portrait Gallery

An incident at the National Portrait Gallery indicates an early interest in the reproduction of Auricular frames. In May 1871, George Scharf, then the Secretary of the Gallery [6], received the 5th Earl Spencer’s permission to copy frames at Althorp, Northamptonshire. Henry Critchfield, of 35 Clipstone Street, now Great Portland Street, London, who also provided extensive services to the National Gallery [7], then received an order to visit the house and the following month, produced an estimate for new ‘Sunderland frames’, a reference to Robert Spencer, 2nd Earl of Sunderland (1641-1702), diplomat, statesman and the creator of the Althorp gallery, whose name became attached to the most developed form of the British Auricular frame. Critchfield estimated for the reframing of two portraits in the National Portrait Gallery, neither of which is today framed in this style, so the frames – if ordered – have disappeared [8]. Critchfield and Scharf’s neo-Elizabethan frame made in 1865 for the National Portrait Gallery’s portrait of Bess of Hardwick (c.1600; NPG 203) indicates that antiquarian framing was on the Gallery’s agenda [9].

The Ashmolean Museum

Auricular revivalism also made an appearance at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, in the person of Chambers Hall (1786-1855), who bequeathed drawings and paintings by Raphael and other Old Masters to the University collections in 1855 [10].

Fig. 4 Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), St. Barbara pursued by her father, o/panel, 6⅛ x 8⅛ in (15.5 x 20.7 cm) in a carved & gilded Auricular frame, before 1855, Chambers Hall Bequest (1855), The Ashmolean Museum,Oxford,WA1855

Fig. 5 Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), St Clare of Assisi, o/panel, 5¾ x 8⅝ in (14.6 x 22 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular frame, before 1855, Chambers Hall Bequest (1855), The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, WA1855.179

Fig. 6 Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), The sacrifice of Noah, o/panel, 7⅜ x 11¼ in (18.7 x 28.8 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular frame, after 1855, Chambers Hall Bequest (1855), The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, WA1855.176

Fig. 7 Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), The Annunciation, o/panel, 5½ x 10⅜ in (14.2 x 26.4 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular frame, after 1855, Chambers Hall Bequest (1855), The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, WA1855.171

The Hall Bequest includes four sketches by Sir Peter Paul Rubens of c.1620 in similar Auricular frames, of which two seem to date from Hall’s time and two are probably later (figs 4-7) [11]. Jon Whiteley observes that Hall bought a set of tools in 1828 and that he made and restored frames:

‘All clearly show his taste for frames carved in a variation of the Sunderland pattern which was common in the 17th Century but must have seemed coarse and heavy to his contemporaries.’ [12]

Lowther Castle, Cumbria

Fig. 8 Attributed to the Studio of Sir Peter Lely, Portrait of a lady, o/c, 50 x 40 in (127 x 101.6 cm), ex-Lowther Castle, Cumbria

A portrait of a lady, on the art market in 1989, ascribed to Sir Peter Lely’s Studio, was sold ‘in a Sunderland-type frame’ with a provenance from ‘The Earl of Lonsdale, Lowther Castle’ (fig. 8). The carving is flat, with a mask at the centre of the base, and curious bunches of grapes in the centres of the vertical elements of the frame, which seems to be a 19th century creation [13].

None of these cases heralded a significant re-adoption of the Auricular style for framing relevant 17th century portraits [14]. In fact, and this is probably a result of ignorance, apart from Ham House, I only know of one other collection in which a revival of Auricular picture frame-making can probably be traced and which accordingly forms the substance of this paper.

Kingston Lacy

Fig. 9 Sir Peter Lely (1618-80), Sir Ralph Bankes, c.1665, o/c, 50 x 40½ in (127 x 102.9 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular frame, before 1814-15, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257049

The collection of pictures at Kingston Lacy, Dorset, which was given by Ralph Bankes to the National Trust in 1981, has been described by Alastair Laing as ‘perhaps the oldest established gentry collection of paintings in Britain, many of which can be traced back to lists compiled in the 1650s’ [15].

Fig. 10 Sir Peter Lely (1618-80), Arabella Bankes, Mrs. Gilly, c.1660-65, o/c, 50 x 40 in (127 x 101.6 cm), in its original carved & gilded Auricular frame, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257043

Fig. 11 After Sir Peter Lely (1618-80), Mary Bankes, Lady Jenkinson, c.1660-65, o/c, 50 x 40 in (127 x 101.6 cm), in its original carved & gilded Auricular frame, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257047

Fig. 12 Sir Peter Lely (1618-80), ‘Mr Stafford’: almost certainly Edmund Stafford of Buckinghamshire, c.1660-65, o/c, 50 x 40½ in (127 x 102.9 cm), in its original carved & gilded Auricular frame, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257044

Fig. 13 Sir Peter Lely (1618-80), Elizabeth Trentham, Viscountess Cullen, c.1660-65, o/c, 50 x 40½ in (127 x 102.9 cm), in its original 17th century carved & gilded Auricular frame, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257046

Its founder, the builder of the house [16], Sir Ralph Bankes (1631-77; fig. 9) [17], was a friend of Sir Peter Lely, and four Lely portraits, all of c.1660-65, survive in 17th century Auricular frames: two of Sir Ralph’s sisters, Arabella Bankes, Mrs. Gilly (NT 1257043; fig. 10) and Mary Bankes, Lady Jenkinson (NT 1257047; fig. 11); together with ‘Mr Stafford’: probably Edmund Stafford of Buckinghamshire (NT 1257044; fig. 12) [18] and Elizabeth Trentham, Viscountess Cullen (NT 1257046; fig. 13), who was ‘notorious for her beauty, extravagance and immorality’ [19].

Fig. 14 Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Sir John Borlase, c.1637-8, o/c, 54 x 42½ in (137.2 x 108 cm) in its original carved & gilded Auricular frame, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257065

Fig. 15 Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Lady (Alice) Borlase, c.1637-8, o/c, 54 x 42½ in (137.2 x 108 cm), in its original carved & gilded Auricular frame, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257066

Sir Oliver Millar noted of the pair of Van Dyck portraits of Sir John Borlase and Sir Ralph Bankes’s sister, Lady (Alice) Borlase (c.1637-8; NT 1257065- 6), that they are the earliest paintings at Kingston Lacy to have coeval ‘fine Auricular frames’ (figs 14-15) [20].

Fig. 16 Studio of Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Charles I, late 1630s, o/c, 54⅝ x 43¾ in (138.7 x 111.1 cm), in its original carved & gilded Auricular frame, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257097

Fig. 17 Studio of Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Henrietta Maria, late 1630s, o/c, 53¼ x 43¼ in (135.2 x 109.8 cm) in its original carved & gilded Auricular frame, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257101

The pair of Van Dyck studio portraits of Charles I (NT 1257097) and Henrietta Maria (NT 1257101) have similar frames of approximately the same date (figs 16-17).

Fig. 18 Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627-78), Trompe l’oeil of a framed necessary-board, 1662-63, o/panel, 21¼ x 23¼ in (54 x 59.1 cm), Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257236

The collection also includes a trompe l’oeil by Samuel van Hoogstraten, depicting a necessary-board within an Auricular frame (1662-3; NT 1257236; fig. 18), which was probably at Kingston Lacy by 1731 and certainly by 1814-15 [21]. Indeed, Kingston Lacy is one of the Trust’s houses, like Ham House and Chirk Castle, North Wales, in which Auricular frames abound. At Ham and Chirk, each panel of the Long Gallery’s woodwork, dating from the 1630s and the 1670s respectively, is hung with a portrait in an Auricular frame.

Sir Peter Lely’s The Penitent Magdalen

Fig. 19 Sir Peter Lely (1618-80), Nicholas Wray, c.1655, o/c, 45 x 33 in (114.3x 83.8 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257102

Fig. 20 Sir Peter Lely (1618-80), The penitent Magdalen, c.1650-55, o/c, 64¼ x 55⅝ in (163.2 x 141.3 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, partly c.1760?, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT1257099

Sir Ralph Bankes paid, before 1659, ‘£20’ each ‘w[i]th frames’ to Lely for a portrait of the copyist, Nicholas Wray (NT 1257102; fig. 19), and for one subject picture, The penitent Magdalen, (NT 1257099; fig. 20) [22]. So are we looking at original ‘Lely’ frames around these two pictures? The answer has to be ‘No’. The Wray portrait frame has clearly been cut and lengthened at the sides with a somewhat alien section of Auricular style carving, typical of unexplained and eclectic alterations to other frames in the house.

Fig. 21 Fragments of an Auricular frame, carved & gilded wood, Kingston Lacy, Dorset.

A list of leftover ‘Marbles and Carvings’ at Kingston Lacy compiled in 1858 reveals that they included frames and parts of frames. Elements of dismantled Auricular frames survive (fig. 21) [23]. The canvas of Lely’s The Penitent Magdalen has been extended by just over eight inches on the left and the frame has been extensively altered. The obvious areas of alteration are in the cresting and in the equivalent section, including the mask, at the base (fig. 20). Neither looks 17th century, nor does the style of the carving.

Fig. 22 Fragments of a picture frame incorporating a male mask similar to that of the frame of Lely’s The penitent Magdalen.

A fragment of a similar male mask (NT1256744.2.2; fig. 22) suggests that The penitent Magdalen frame was originally one of a pair.

The history of the display of The penitent Magdalen can be traced in some detail. In Sir Ralph Bankes’s chambers at Gray’s Inn, London, it was part of a collection of 36 pictures, which were listed in 1659 [24]. At Kingston Lacy, the picture was first recorded in 1731, when it was treated by George Dowdney, a painter and restorer [25]. It was hanging in the Great Parlour in 1762 and 1772 [26], together with the rest of the Lelys, which indicates that it was hung in conformity with them and so was probably still its original size. The Lely series was seen in 1762 by Sir Joshua Reynolds, who wrote: ‘I never had fully appreciated Sir Peter Lely until I had seen these portraits’ [27].

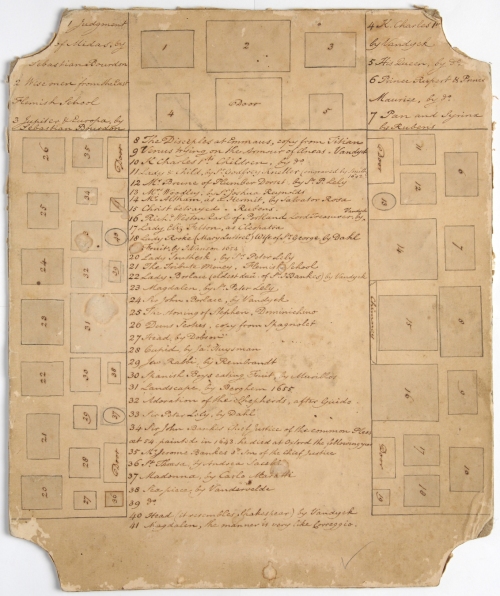

The pre-1814-15 picture-hanging diagrams

Fig. 23 Picture-hanging plan of the Saloon at Kingston Lacy, showing Lely’s Penitent Magdalen (no. 23; centre top), already extended in size, flanked by two ‘50 x 40 in.’ Van Dyck portraits (nos 22 and 24) of Sir John and Lady Borlase, before 1814-15, ink & watercolour on paper, mounted on card, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1253625.

A picture-hanging diagram of the Saloon on a paper remnant of a hand-screen (NT 1253625; fig. 23), one of three made before 1814-15 [28], shows for the first time the size of The penitent Magdalen in relation to other paintings [29]. Flanking it was the pair of portraits by Van Dyck of Sir John Borlase and his wife, Lady Borlase (1637-8; figs 14-15) in their original Auricular frames. The Van Dyck portraits are accurately depicted in the hanging diagram as being smaller than Lely’s extended The Penitent Magdalen. They measure 54 x 42½ in., and The Penitent Magdalen measures 64¼ x 55⅝ in. after its extension by 8¼ in. on the left side. This alteration had already been carried out when the hand-screen diagram was made, so the presumption must be that the present frame was already around the painting.

The 18th century origins of the Auricular revival at Kingston Lacy

Fig. 24 George Dowdney (fl. 1730s), Henry I Bankes, dated 1734 on reverse, o/c, 29½ x 23¾ in (75 x 60 cm), Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257151

Henry I Bankes (1698-1776) commissioned George Dowdney to clean and restore the Kingston Lacy pictures in 1731. Dowdney’s list is the first record of the pictures in the house and he painted Bankes’s portrait in 1734 (NT 1257151; fig. 24) [30]. Henry I himself listed the pictures at Kingston Lacy in 1762 (revised 1775) and 1772, and to him has been ascribed the inauguration of the Auricular revival in picture frames there. In 1994, Alastair Laing stated that:

‘It was probably also Henry [I] who had so many of the pictures framed or reframed, probably by local craftsmen, and often with imitations of the superb 17th century ‘Sunderland’ frames on Sir Ralph’s Peter Lelys. These are the first such historicizing frames dating from the 18th century to have been identified anywhere.’ [31]

The Auricular revival frames at Kingston Lacy may indeed derive from the 18th century [32]. In 1986, John Cornforth also noted that ‘a number of the frames in the Auricular style incorporate mid-18th– century ornamental motifs, as if they were 18th-century essays in the 17th-century style’ [33].

Fig. 25 After Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), The Princes of the Palatinate, o/c, 54 x 58 in (137.2 x 147.3 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, c.1760?, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257115

Fig. 26 After Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), The three eldest children of Charles I, o/c, 48 x 54 in (121.9 x 137.2 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, c.1760?, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257117

The frames of two portraits after Van Dyck, The Princes of the Palatinate (NT 1257115; fig. 25) and The three eldest children of Charles I (NT 1257117; fig. 26) have crestings which are markedly rocaille. If these two frames date from around 1760, then the inserted cresting and the central section below, including the mask, of Lely’s extended The penitent Magdalen (figs 20 & 22), may be contemporaneous. Fragments of frames in store may also date from that period (figs 21-22).

Fig. 27 Massimo Stanzione (1585-1656), Jerome Bankes, Naples, c.1655, o/c, 50 x 40 in (127 x 101.6 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, partly c.1760?, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257045

The inserted top central section of the frame of Massimo Stanzione’s portrait of Jerome Bankes (fig. 27) seems also to be be an 18th century survival, and the inspiration for the crestings of the Auricular revival frames which were presumably made for the Library before 1814-15.

Fig. 28 Studio of Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Richard Weston, 1st Earl of Portland K.G., o/c, 84 x 48 in (213.4 x 121.9 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, before 1814-15, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257109

Fig. 29 Edward Altham (1622-94), Self-portrait as a hermit, Rome, c.1680-90, o/c, 93 x 65 in (236.2 x 165.1 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, before 1814-15, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257111

Cornforth illustrated two examples of what he felt might be 18th century revivalist frames: around the portrait after Van Dyck of Richard Weston, 1st Earl of Portland, KG (NT 1257109; fig. 28) and the self-portrait of Edward Altham as a hermit (NT 1257111; fig. 29) [34]. However, Henry I Bankes’s grandson, William Bankes (1786-1855), declared that he intended ‘to alter all the library frames and Lord Portland and Mr Altham to correspond with Charles and his Queen [Van Dyck Studio; figs 16-17] and Sir J. and Lady Borlase [by Van Dyck; figs 14-15]’, all four of which retain their original 17th century Auricular frames [35]. This would suggest that the two matching frames around the portraits of ‘Lord Portland and Mr Altham’, which have hung together in the Saloon since 1762, were probably made for the pictures when the Library was also rehung before 1814-15.

Fig. 30 After Guido Reni (1575-1642), The Adoration of the Shepherds, o/c, 48 x 36 in (121.9 x 91.4 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, c.1760?, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257096

Fig. 31 Jacob Huysmans (c.1630-96) after Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Cupid preparing his bow, before 1659, o/c, 52 x 40 in (132.1 x 101.6 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, c.1760?, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257118

Two other paintings – The adoration of the shepherds and Cupid preparing his bow – are in matching Auricular revival frames (figs 30-31), with rocaille crestings and a prominent shell below. Apart from the additions to the sides, these two frames probably date from the 18th century, like the other similar frames and parts of frames that have already been noted, particularly the frames of the two group portraits after Van Dyck (figs 25-26). Their crestings are also similar to that of Lely’s The penitent Magdalen (fig. 20). The first is a copy (NT 1257096), adapted to a rectangular format, after Guido Reni’s octagonal The adoration of the shepherds, once in the Walpole Collection at Houghton, Norfolk, and now in the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow (inv.1608) [36]. The Reni copy (fig. 30) made its first appearance at Kingston Lacy in the Saloon picture-hanging diagram, drawn up before 1814 to 1815 (fig. 23).

Fig. 32 Nicolaes Berchem the elder (1620-83), Landscape with herdsmen, s & d 1655, o/c, 86 x 72 in (218.4 x 182.9 cm), in a carved & gilded early 19th century frame, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257110

It was then hanging to the right of Berchem’s large Landscape with herdsmen (fig. 32), which Sir Ralph Bankes acquired through Sir Peter Lely and which was re-framed in the early 19th century (not in Auricular style), as part of a group that included Lely’s The penitent Magdalen (above the Berchem), flanked by the Van Dyck portraits of Sir John Borlase and Lady Borlase. The adoration of the Magi may then already have been in its present frame in view of the adjacent 17th century and later Auricular style frames. Huysmans’s Cupid preparing his bow (NT 1257118; fig. 31), has been in the Bankes collection since the 17th century [37]. It was also listed in the Saloon in the 1814-15 picture-hanging diagram. By 1856, both pictures were in the North Parlour, when the Huysmans Cupid was clearly in the same frame (‘in gilt frame with large carved ornament over’) [38], and by 1905, both pictures were back in the Saloon [39].

19th century Auricular revival frames

Fig. 33 Pompeo Batoni (1708-87), Henry II Bankes, Rome, s & d 1779, o/c, 39 x 28½ in (99.1 x 72.4 cm), Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257055

The squire of Kingston Lacy from 1776 to 1834 was Henry II Bankes (1757-1834), politician and historian, who was painted by Batoni in Rome in 1779 (NT 1257055; fig. 33), and who was interested in pictures and Old Master drawings.

Fig. 34 The Saloon, Kingston Lacy, Dorset (NT)

He altered and redecorated the Saloon (the Great Hall of the 17th century house) in the 1780s, when it was already the main room for hanging pictures (fig. 34). The pre-1814-15 picture-hanging diagrams revealing the changes to the display of the Saloon, Library and Billiard Room, including the extension of Lely’s The Penitent Magdalen, are possibly in the handwriting of Henry II Bankes, but the picture hangs were presumably devised in consultation with his son, William Bankes (1786-1855), who was vigorously collecting paintings for the house in the early 19th century and who – after his father’s death in 1834 – transformed Kingston Hall, which he renamed Kingston Lacy, in honour of a prominent medieval owner of the estate [40].

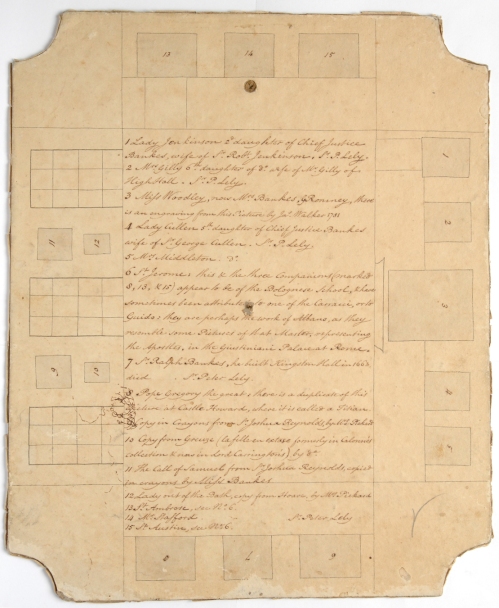

The Library

Fig. 35 The Library, Kingston Lacy, Dorset (NT)

Fig. 36 Picture-hanging plan of the Library at Kingston Lacy, before 1814-15, ink & watercolour on paper, mounted on card, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1253624

In the Library, we have proof that alterations were made to the Auricular frames of the paintings hung above the bookcases (fig. 35) and that the hang was enriched before 1814-15, the date of one of the three picture-hanging diagrams (fig. 36).

Fig. 37 Attributed to Gerard Seghers (1591-1651), St. Ambrose, o/c, 45 x 56 in (114.3 x 142.2 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, before 1814-15, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257057

Fig. 38 Attributed to Gerard Seghers (1591-1651), St. Jerome, o/c, 45 x 56 in (114.3 x 142.2 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, before 1814-15, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257048

Fig. 39 Attributed to Gerard Seghers (1591-1651), St. Augustine of Hippo, o/c, 45 x 56 in (114.3 x 142.2 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, before 1814-15, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257059

Fig. 40 Attributed to Gerard Seghers (1591-1651), St. Gregory the Great, o/c, 45 x 61 in (114.3 x 154.9 cm), in a carved & gilded Auricular revival frame, before 1814-15, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257050

The room was then hung, much as it is now, with six Lely portraits and four larger paintings of Doctors of the Western Church, attributed to Gerard Seghers, also in Auricular style frames (NT 1257057; 1257048; 1257059 and 1257050; figs. 37-40) [41].

William Bankes commended his father’s taste in moving the Lelys to the Library above the bookcases: ‘the fine family portraits are admirably placed in it [the Library], and I should be at a loss how to dispose them elsewhere’ [42]. However, he proposed ‘to alter all the library frames…to correspond with Charles and his Queen (figs 16-17) and Sir J. and Lady Borlase (figs 14-15)’ [43]. Although the four Lely portraits flanking the Library chimneypiece are in almost matching 17th century ‘Sunderland’ Auricular frames, the two Lely portraits on the end walls, each hung between two Doctors of the Western Church by Seghers, have frames with distinctive pierced crestings and with shells in the centre beneath. These two Auricular revival frames around portraits of Sir Ralph Bankes and his wife’s uncle, Charles Brune [44], correspond in style to the frames around the four Doctors of the Western Church. These changes were presumably made before the 1814-15 picture-hanging plan of the Library (fig. 36) [45].

Now hanging over the Library chimneypiece is Stanzione’s brooding portrait, painted at Naples c.1655, of Jerome Bankes (NT 1257045; fig. 27), Sir Ralph’s younger brother. This has the same type of pierced cresting that has already been doubted as 17th century, and the frame has been cut in several places [46].

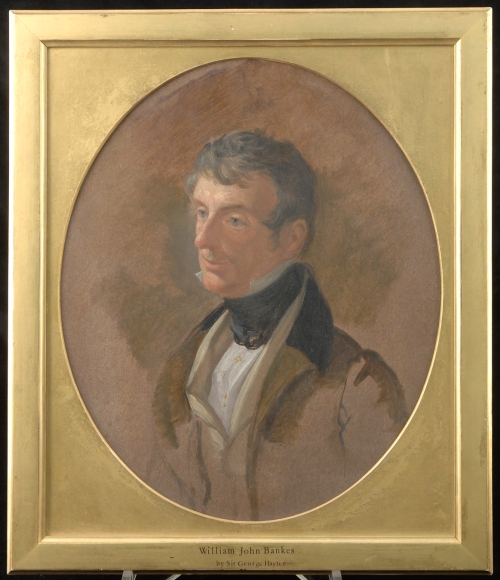

Fig. 41 George Sandars (1774-1846), William John Bankes, 1812, watercolour on ivory, 11½ x 9½ in (29 x 23.6 cm), Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1251251

Fig. 42 Sir John Hayter, R.A., (1792-1871), William John Bankes, 1833, oval, o/board, 11½ x 9¼ in (28.5 x 23.5 cm), Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257128

Henry II Bankes continued his father’s revivalist taste for the Auricular during his rearrangement of the collection under the influence of his son, William Bankes (figs 41-42). The arrangements of father and son are recorded in the 1835 inventory, whereas the 1856 inventory [47], drawn up after the death of William’s brother, George, who only outlived him by a year, is the document which charts William’s further embellishments. These were on a grand scale. From 1835-41, William Bankes employed Charles Barry to transform the interior, which was further elaborated by refined Italian carvers and by Baron Marochetti’s bronzes celebrating the Bankes’s loyalty to the crown during the Civil War. The Emperor Augustus’s supposed boast about Rome is inscribed above one of the Staircase landing doorcases, beneath his Antique portrait bust: ‘I found it brick and left it marble’, which is very much what Bankes achieved in his transformation of Pratt’s 17th century house.

William Bankes, the contemporary of Byron at Trinity College, Cambridge, traveller in Egypt and the Levant, and – thanks to his friendship with the Duke of Wellington – a precocious collector of Spanish paintings during the Peninsular War, was almost entirely responsible for the acquisition of the Old Masters at Kingston Lacy, which include paintings by Sebastiano del Piombo Titian, Tintoretto, Rubens and Velázquez [48]. Like his father, he concentrated his best pictures in the Saloon, where his Spanish pictures were hanging in 1835 (fig. 35). He also took a close interest in picture frames.

Fig. 43 Circle of Raphael, The Holy Family with the infant St. John in a landscape, ‘The Kingston Lacy Raphael’, c.1516-17, o/panel, 30 x 21 in (76 x 53.3 cm), carved walnut frame by Pietro Giusti of Siena, 1853-6, Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257083

His premier commission was the almost surreally precise carved walnut frame for the so-called ‘Kingston Lacy Raphael’, The Holy Family with the infant St. John in a landscape, now demoted to Circle of Raphael, which he commissioned from Pietro Giusti of Siena in 1853 (NT 1257083; fig. 43) [49]. Might Bankes have known Chambers Hall, whose Auricular revival frames survive in the Ashmolean (figs 4-5) and who published a book about the peregrinations of a Raphael Holy Family, perhaps inspired by the ‘Kingston Lacy Raphael’ [50]?

In 1841, following his second arrest for a homosexual act in a public place, Bankes fled to France and then to Italy, basing himself in Venice. He was outlawed, but the family tradition is correct that in 1854, when he may have had a terminal illness, he came surreptitiously to Kingston Lacy to inspect his continuing works there [51].

Fig. 44 The ‘Spanish Picture’, ‘Golden’ or Spanish Room, 1838-55, Kingston Lacy, Dorset (NT)

For the framing of three of his Spanish pictures in what he called the ‘Spanish Picture’ or ‘Golden’ Room (fig. 44), Bankes employed the Venetian carver, Giuseppe Foradori, who made – in Bankes’s own words – the ‘gloriously carved frames for the three central pictures’, then above and flanking the chimneypiece, which were made in Venice and were being gilded in London in November 1850 [52].

Fig. 45 Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) & studio, Philip IV of Spain, c.1626-8, o/c, 78½ x 42½ in (199 x 108 cm), sold 1896 from Kingston Lacy, still in the giltwood frame made by Giuseppe Foradori in Venice & gilded in London (November 1850), Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts; P26e18

Among them and still in Bankes’s frame was the lost jewel of the collection, sold in 1896 to Isabella Stewart Gardner and now in her Museum in Boston (P26e18): Velázquez’s full-length portrait of Philip IV of Spain (fig. 45). Bankes described these frames as being ‘in the Venetian manner’ [53]. The decoration of the room is indeed more Venetian than Spanish, incorporating a ceiling and gilded leather hangings from the palazzo Contarini degli Scrini, Venice.

Fig. 46 Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo (c.1612 – 67), o/canvas, reduced sketch after Velázquez’s Las Meninas (Prado, Madrid), 56 x 48 in (142.2 x 121.9 cm), in giltwood frame made by Giuseppe Foradori in Venice & gilded in London (November 1850), Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257140

Fig. 47 Attributed to Francisco de Zurbarán (1598 -1664) Saint Augustine, Bishop of Hippo (354-430) in meditation, c.1620-24, o/c, 90 x 51 in (228.6 x 129.5 cm), in giltwood frame made by Giuseppe Foradori in Venice & gilded in London (November, 1850), Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257131

Foradori’s remaining two picture frames are of a similar ‘Sansovino’ character. They were designed for Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo’s reduced oil sketch after Velázquez’s Las meninas (NT 1257140; fig. 46) and Saint Augustine, Bishop of Hippo (354-430) in Meditation (NT 1257131; fig. 47) attributed to Francisco de Zurbarán.

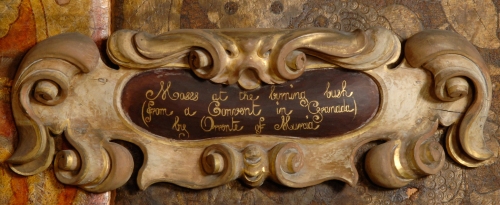

Fig. 48 Carved, painted & gilded cartouche in the Auricular style in the Spanish Room at Kingston Lacy, 1838-55, 23¾ x 55½ in (60 x 140.7 cm), carved, painted & gilded wood, NT 1254746.4, which is fixed above Pedro Orrente (1588-1645), ‘Moses at the burning bush’, o/c, 10½ x 42½in (26.7 x 107.9 cm), Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257137

Fig. 49 Carved, painted & gilded cartouche in the Auricular style in the Spanish Room at Kingston Lacy, 1838-55, 23¾ x 55¼ in (60 x 140.5 cm), carved, painted & gilded wood, NT 1254746.5, which is fixed above Pedro Orrente, ‘Samson with the lion’, o/c, 10½ x 42½ in (26.7 x 107.9 cm), Kingston Lacy, Dorset, NT 1257138

The Auricular style makes an unexpected entry into the Spanish Room’s eclectic décor in the form of two complementary but not identical cartouches, fixed above a pair of oblong pictures by Pedro Orrente (figs 48-49). With their even grander companions in a more marked ‘Sansovino’ style, they are among the most elaborate picture labels ever made.

There is therefore at Kingston Lacy compelling evidence of Auricular revivals. It is to be hoped that these initial investigations will be borne out by physical evidence during examination of the frames and by documentary proof when the Kingston Lacy archive is more thoroughly investigated.

***********************************************

Christopher Rowell is the National Trust’s Curator of Furniture (2002-); Chairman of the Furniture History Society (2013-); and a member of the UK Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (2015-). He has published widely on collections, furniture, historic interiors and the display of art. He was editor and principal contributor to Ham House: 400 Years of Collecting and Patronage (Yale University Press, 2013), which was shortlisted for the 2014 Berger Prize for British Art History. His contributions to the second book in the series – David Adshead and David A.H.B. Taylor, eds, Hardwick Hall: A Great Old Castle of Romance, published in November 2016 – include an appendix on the picture frames at Hardwick.

***********************************************

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am particularly grateful to Reinier Baarsen, Luke Dady, James Grasby, Alastair Laing, Nicholas Penny, Jacob Simon and David Taylor for generous advice and for their helpful comments on the text. I am also indebted to Nicholas Penny for allowing me to consult his frame archive at the National Gallery and to Wolf Burchard for assistance in various ways.

[1] Christopher Rowell, ‘National Trust Acquisitions 2002-2003: Silver for Uppark’, Apollo, vol. CLVII, April 2003, p. 54.

[2] Jacob Simon, Picture Frames at Ham House, Swindon 2014, p. 17. For 17th century picture frames at Ham House, see also Jacob Simon, ‘Picture Framing at Ham House in the Seventeenth Century’, in Christopher Rowell, ed., Ham House: 400 Years of Collecting and Patronage, New Haven & London 2013, pp. 144-157.

[3] Alastair Laing & Nino Strachey, ‘The Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale’s Pictures at Ham House’, Apollo, vol. CXXXIX, May 1994, pp. 3-9.

[4] Simon 2014, p. 21.

[5] See inter alia, Christopher Rowell, ‘Romantic Antiquarianism at Ham House (1799-1878)’, and Michael Hall, ‘Bodley and Garner and Watts & Co: Repairs and Renovation at Ham House for William Tollemache, 9th Earl of Dysart’, in Rowell 2013, pp. 360-73 & pp. 374-82.

[6] Peter Jackson, ‘Scharf, Sir George (1820–1895)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Sept 2010 [http://www.oxforddnb.com.ezproxy2.londonlibrary.co.uk/view/article/24796, accessed 17 Aug 2016]

[7] Critchfield was employed at the National Gallery from 1854 until his dismissal in 1880; see Jacob Simon, ‘Framing Italian Renaissance Paintings at the National Gallery, London’.

[8] I am grateful to Jacob Simon for this information and for sending me details of these two pictures: Queen Anne; William, Duke of Gloucester, after Sir Godfrey Kneller, Bt., o/c, (c.1694) 48 in. x 39 1/2 in. (121.9 x 100.3 cm), purchased 1871 (NPG 325); and Prince George of Denmark, Duke of Cumberland, after John Riley, o/c (1687?), 49 in. x 40 in. (124.5 x 101.6 cm), purchased 1871 (NPG 326).

[9] Jacob Simon, The Art of the Picture Frame: Artists, Patrons and the Framing of Portraits in Britain, exh. cat. (National Portrait Gallery, London), London 1996, cat. no. 98, pp. 179-80, & fig. 120, p. 112.

[10] Christopher White, ‘Hall, Chambers (1786–1855)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (accessed 12 Oct 2016).

[11] The two in pre-1855 frames are the smaller of the four: Sir Peter Paul Rubens, St. Barbara pursued by her father (WA1855.178); and St. Clare of Assisi (WA1855.179). The other two Rubens sketches are: The sacrifice of Noah (WA1855.176) and The Annunciation (WA1855.171). For a detailed discussion and analysis of the Auricular and Auricular revival frames around these paintings, see Timothy Newbery and Jevon Thistlewood, ‘An Auricular frame amongst the Founder’s Collection of the Ashmolean Museum’.

[12] Jon Whiteley, ‘The Chambers Hall Letters’, Ashmolean Magazine, no. 64, Summer 2012, pp. 25-6. I am very grateful to Jacob Simon for informing me of Chambers Hall’s interest in the Auricular style and for sending a copy of Jon Whiteley’s article and photographs of relevant frames.

[13] Christie’s, London, 25 September 1989, lot 321, 50 x 40 in (Nicholas Penny Frame Archive, The National Gallery, London). I am grateful to Sharon Goodman for attempting to locate a publishable image of this painting at Christie’s, London.

[14] For an interesting 20th century episode of Auricular revival, see Caroline Oliver, ‘Frank Salisbury and the Auricular Frame’, 17 October 2016. Frank Owen Salisbury (1874-1962) was a fashionable portrait painter.

[15] Alastair Laing, ‘The Pictures and Sculpture’ in Anthony Mitchell, ed., Kingston Lacy, London 1994, revised ed. 2008, pp. 37-43, p. 37.

[16] For the architectural history of Kingston Lacy, which was designed by Sir Roger Pratt, see Mitchell 1994 and new, revised ed., 1998.

[17] Sir Ralph Bankes was born on 25 November 1631, according to an entry in a family bible (D-BKL/H/A/78); a fact kindly transmitted by Luke Dady.

[18] See Alastair Laing, ‘Sir Peter Lely and Sir Ralph Bankes’ in David Howarth, ed., Art and Patronage in the Caroline Courts, Cambridge 1993, pp. 107-31.

[19] Alastair Laing, Kingston Lacy: Illustrated List of Pictures, p. 8; see also Mitchell 1994, p. 48.

[20] Susan J. Barnes, Nora de Poorter, Oliver Millar and Horst Vey, Van Dyck: A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings, New Haven and London 2004, cat. nos. IV.29-30, p. 449 (entry by Oliver Millar).

[21] It must be ‘6. Medley by Samuel Hoogstraten’ in a picture-hanging diagram of 1814-15 of the room listed as the Billiard Room in 1835 (the companion of similar diagrams of the Saloon and Library, figs 23 and 36). It is possibly identifiable with ‘92. A peice of still life [£]0 5[s] 0[d]’ in a list of 128 paintings attended to in 1731 by the portrait painter and picture cleaner, George Dowdney, at a total cost of £56 15s (copy in the National Trust’s study collection of an original document in the Bankes Archive, deposited by the National Trust in the Dorset History Centre, Dorchester). John Cornforth connected the unsigned and undated list with an identical payment to George Dowdney, whose portraits of John II Bankes (1733; NT 1257149) and Henry I Bankes (1734; NT 1257151) are listed in the North Parlour in the 1762 inventory (John Cornforth, ‘Kingston Lacy Revisited – II’, Country Life, 24 April 1986, p. 1123).

[22] ‘A Noate of my Pictures & w[ha]t they cost w[i]th frames [undated]’, handwritten list by Sir Ralph Bankes (copy in the National Trust’s study collection of an original document in the Bankes Archive, deposited by the National Trust in the Dorset History Centre, Dorchester). This document is published in Laing 1993, pp. 121-2.

[23] ‘1858 A List of Marbles and Carvings &&c in the [Carpenters’] Shop and Store Rooms at Kingston Lacy’ (copy in the National Trust’s study collection of an original document in the Bankes Archive, deposited by the National Trust in the Dorset History Centre, Dorchester).

[24] The penitent Magdalen appears in four relevant documents: ‘Pictures in my Chamber att Grayes Inne’, ‘A Noate of my Pictures & w[ha]t thay Cost w[i]th frames’ ‘A Noate of my Pictures at Grayes Inn and what they Cost Xber [October] ye 23rd 1659’ and ‘The Value of my Pictures’; handwritten lists by Sir Ralph Bankes (copies in the National Trust’s study collection of original documents in the Bankes Archive, deposited by the National Trust in the Dorset History Centre, Dorchester). Transcriptions of these documents are published in Laing 1993, pp. 121-5.

[25] It was presumably ‘99. A Magdalen [£]0 5[s] 0[d]’ listed in 1731 by the portrait painter and picture cleaner, George Dowdney (see note 19 above).

[26] The present Drawing Room; the picture was moved to the Great Hall – the present Saloon – before 1814-15, then to the Billiard Room by 1835 and was listed again in the Saloon, where it remains, by 1856.

[27] Quoted in Anthony Mitchell, Kingston Lacy, London 1986 (second revised ed., 1987), p. 14.

[28] The dating of the Saloon picture-hanging plan, and two others also made for hand-screens, delineating the hangs in the Library and the future Billiard Room (described as such in the 1835 inventory), depends mainly on the fact that no Spanish picture is listed, apart from the copy of Murillo’s Two urchins eating melons and grapes, which had been in the Bankes collection since 1659 (NT 1257134, after the original of 1645-6 in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, inv. No. 605). William Bankes started collecting Spanish paintings during the Peninsular War in 1813 and sent his first Spanish picture home in 1814. Bankes’s Spanish pictures were hanging in the Saloon in 1835 and were subsequently concentrated in the Spanish Room (created 1838-55). All three plans are mounted on card, with on the reverse, a bistre engraving of a young woman’s head after François Boucher (1703-70) by Gilles Demarteau (the Saloon and Library) and by Louis Bonnet (the Billiard Room); copies of these engravings are in the Louvre, Paris, Réserve Edmond de Rothschild (19264 LR/ Recto; 19232 LR/ Recto 19061 LR/ Recto respectively).

[29] The penitent Magdalen was then the centrepiece of the upper register of the wall opposite the fireplace.

[30] For Dowdney’s picture list, see note 19.

[31] Mitchell 1994 (chapter by Alastair Laing), p. 39.

[32] Mitchell 1987, p. 14, describing the Auricular revival frames in the Library, writes that they were: ‘perhaps carved for the 18th century collection, [and] were altered by William [Bankes] in the 19th century ‘to correspond’’.

[33] John Cornforth, ‘Kingston Lacy Revisited – II’, Country Life, 24 April 1986, p. 1126, figs 6-7.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Quoted in Mitchell 1987, p. 28, where no date is given for the quotation. The relevant document has not been identified in the Bankes Archive in the Dorchester History Centre, but presumably dates before 1814-15, when the Library picture hanging diagram was made (fig. 36 and see notes 27-8).

[36] It was sold to Empress Catherine II of Russia, Catherine the Great, for £400 in 1779; see Andrew Moore, ed., Houghton Hall: The Prime Minister, The Empress and The Heritage, 1996, p. 100.

[37] Ralph Bankes (1631?- 1677) recorded in 1659 that he bought ‘A Cupid of Huysmans’ from ‘Mr Mathewes’ for £5, Laing 1993, p. 123. The entry on the picture in National Trust Collections online explains the picture’s subject: The pretext for the picture appears to be the passage in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book V, vv.355 ff., Pluto having surfaced from the underworld to circumnavigate Sicily in his chariot to see what damage had been wrought by his struggles to free himself, is sighted by Venus. She promptly urges her son Cupid, to bring about the union of Pluto and Proserpine. Cupid then ‘selected one of his thousand arrows, the sharpest and surest, and most obedient to the bow. Then, bending his pliant bow against his knee, he struck Pluto to the heart with the barbed shaft’.

[38] D-BKL/G/B/66: ‘Inventory of Sundry Furniture, Pictures, Plate, Linen, China & Glass, Books, Wine, and effects, on the premises Kingston Lacy, Dorset, the property of the late Rt. Honble Geo. Bankes, M.P,’ July 1856. There are two copies of this inventory.

[39] ‘An Inventory of Heirlooms at “Kingston Lacy” Wimborne, Dorset. 1905 [by] Tho[ma]s Vigers, Valuer &c, 3 Eccleston Street, London S.W,’ D-BKL/G/B/62.

[40] Luke Dady, Archives Services Officer (Bankes), Dorchester History Centre, kindly observes (written communication) that: ‘the writing looks to me to be more akin to Henry’s than William’s. However, as your email suggests, the two can be quite similar, and I could be wrong (and William’s writing when he was younger was generally much better than his later style!)’.

[41] The four Doctors of the Western Church were previously the only pictures in the Drawing Room, while the Lelys were hung together in the adjoining Great Parlour.

[42] Mitchell 1987, p. 14; the quotation, as published, is not dated and it has not yet proved possible to identify it among the voluminous documents in the Bankes Archive in the Dorchester History Centre. The same quotation is also not dated in Cornforth 1986, p. 1126.

[43] Quoted in ibid., p. 28. The date of this statement is not given (see previous note).

[44] This portrait was in the Saloon in 1814-15, 1835 and 1856 and in the pre-1814-15 picture-hanging plan its present position on the end wall of the Library was taken up by Lely’s portrait of ‘Mr Stafford’ (fig. 12).

[45] In an undated note headed ‘For the Revival of the Sunderland Frame’, Nicholas Penny observes that ‘The portraits by Lely in the library at Kingston Lacy may well be in their original Sunderland frames but the Massimo Stanzione portrait of Jerome Bankes (c.1655) and the fathers of the Latin Church by or attributed to Gerard Seghers must surely have been given frames of this character in the 1840s at the behest (or design) of William Bankes’ (Nicholas Penny Frame Archive, The National Gallery, London).

[46] In 1762, the Stanzione portrait was hanging in the North Parlour with the Lelys and by 1814-15 was in the Saloon, where – together with the Library – the other Auricular frames noted here were placed.

[47] D-BKL/G/B/66.

[48] For a biography of William Bankes, see Anne Sebba, The Exiled Collector: William Bankes and the Making of an English Country House, London 2004; for Bankes as a collector and patron, see also Mitchell 1987 and 1994; Alastair Laing, In Trust for the Nation: Paintings from National Trust Houses, exh. cat. (National Gallery London), London 1985, pp. 231-2; and Alastair Laing, Kingston Lacy: Illustrated List of Pictures, pp. 1-4.

[49] Christopher Rowell, ‘The Kingston Lacy ‘Raphael’ and its Frame (1853-56) by Pietro Giusti of Siena’, The National Trust Houses & Collections Annual 2014, published in association with Apollo, pp. 40-47.

[50] Chambers Hall, The Picture: A Nosegay for Amateurs – Painters – Picture-Dealers – Picture-Cleaners – Liners – Repairers – And all the Craft: being The Autobiography of A Holy Family by Raphael, faithfully written from Actual Dictation of the Picture Itself. by CH, London 1837.

[51] Sebba 2004, pp. 245-6.

[52] Mitchell 1987, p. 36.

[53] Ibid.